by Dr. Howard Johnson (Cultural Historian, UK)

Through the Main Gate: Gwanghwamun

I entered Gyeongbokgung through Gwanghwamun—its grand south gate. It was enormous, dignified, symmetrical. The kind of architecture that seems to say: “Something important lies beyond.”

And something did. But not in the way I expected.

I thought I’d be ushered into opulence. Instead, I found space—empty courtyards, long stone paths, and buildings that stood far apart, almost reluctant to speak. The air didn’t echo. It waited.

It took me a moment to understand: this wasn’t a palace meant to overwhelm. It was a structure designed to humble. The further in you walked, the quieter it became.

It reminded me, strangely, of a British cathedral—not because of its shape, but because of what it withholds. It doesn’t show you the divine. It asks if you’re ready to look for it.

I didn’t just walk under a gate. I walked into a way of thinking.

The Throne Was Not the Center

Geunjeongjeon, the main throne hall of Gyeongbokgung, was the first structure that truly caught me off guard. It is large, certainly. Elevated, imposing, surrounded by stone platforms and lined with markers for ministers and court officials. But something about it felt… exposed.

The king’s throne sits not deep within a sanctum, but in an open, echoing hall. Sunlight floods in from three sides. There’s nowhere to hide. No curtains. No pillars to retreat behind.

I had imagined something more private. But this wasn’t a throne of privilege—it was a platform of responsibility. One where every word could be heard, and every silence noticed.

Behind it, a painted screen: five mountains, two rivers, the sun and moon. I was told it symbolized heaven and earth, balance and eternity. But to me, it also looked like a reminder: that the king sits not above the world, but within it.

Power here was visible, vulnerable, and deliberate. Like standing at the altar, not above it.

Smaller Rooms, Greater Intimacy

After Geunjeongjeon, I expected the palace to get even grander. But it didn’t. It got smaller. Quieter. Closer to the ground.

Sajeongjeon, the council hall just behind the throne room, was simpler—almost modest. It was where the king worked daily with his ministers, away from ceremony. The ceilings were lower. The rooms felt more human.

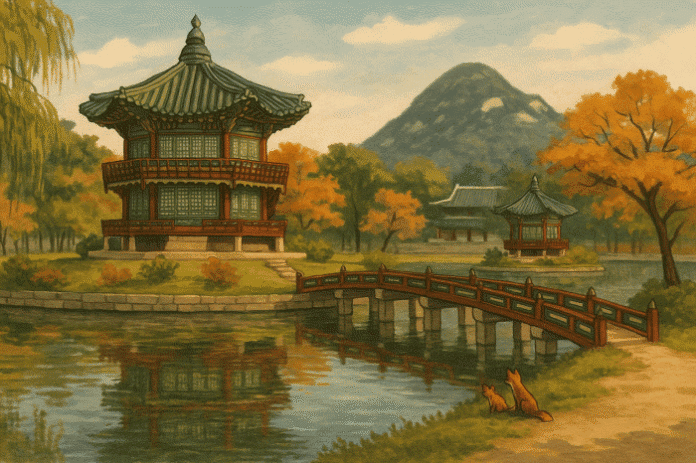

Then came Gyeonghoeru—the raised pavilion overlooking a lotus pond. From afar, it looked like a stage. But up close, it felt like a pause. A place for banquets, yes, but also for watching time float. Water. Reflection. Repetition. It was more philosophy than function.

And finally, I reached Hyangwonjeong—the smallest, most delicate pavilion in the compound. It sat on an island, crossed by a footbridge. The further I went, the more it felt like the palace was guiding me away from power, and toward solitude.

Gyeongbokgung wasn’t leading me inward. It was leading me inwardly.

The Blue Tiles Were Never Just Blue

Everywhere I looked, the rooftops were blue. Not the bright blue of a postcard, but a deep, muted shade—almost contemplative. They glimmered under the sun, but never shouted.

I later learned the tiles were called giwa, and that royal palaces used blue not for flair, but for order. Blue was elemental—representing wood and the east, springtime and renewal. In other words, it wasn’t just beautiful. It was intentional.

The more I noticed them, the more I realized: nothing here was accidental. The spacing of the buildings, the flow of wind, even the patterns in the dancheong—the painted eaves—were governed by logic, not ornament.

It reminded me of British gardens. People think they’re wild, but they’re not. They’re masterpieces of constraint.

Gyeongbokgung was the same. A palace that governs not by gold, but by restraint. Even the silence was curated.

What Power Chose to Leave Empty

Gyeongbokgung is not Versailles. There are no halls of mirrors, no chandeliers, no royal portraits looming over the visitor.

Instead, you find spaces. Empty courtyards. Gravel paths. Wooden beams that creak under your step.

And the sky—always more sky than wall.

At first, it feels bare. Then, it feels honest.

As if the builders of this place believed that power didn’t need to be loud. That reverence was not in what you displayed, but in what you restrained.

In time, I stopped looking for thrones and started noticing thresholds.

The way sunlight angled through the columns. The way the palace opened to the mountains, and the mountains answered back in silence.

That day, beneath the blue roofs, I didn’t just walk through history. I walked through a philosophy—one that left room for me to breathe.